Updated: Jan. 22, 2025

The Myth

For at least 70 years — from 1948 to 2018 — the near-consensus of the scientific community about the person who discovered the first confirmed artificial nuclear transmutation was wrong. An illustrated example of the myth appears in a frame of a 1948 comic book produced by the General Electric Co. The book, Adventures Inside the Atom, was sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to promote the new age of atomic energy.

The book begins in ancient Greece with Aristotle and the concept of the atom. Eventually, the story arrives at the University of Cambridge, in the laboratory of Ernest Rutherford.

Example of the myth of Rutherford's discovery of artificial nuclear transmutation, 1948, General Electric Co.

According to the myth, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with energetic alpha particles and, in doing so, became the world’s first successful alchemist, changing the element nitrogen into the element oxygen.

He did no such thing.

Instead, Patrick Blackett did. In the autumn of 1921, Blackett had earned his undergraduate degree in physics at Cambridge and started working as a research postgraduate student under Rutherford. Rutherford assigned the project to Blackett who then performed the experiment, obtained the data, analyzed it correctly, and published it in a journal article in 1925. Science writer Steven Krivit uncovered this myth in March 2014 during a conversation with John Campbell, a Rutherford historian.

Krivit was having difficulty locating the paper in which Rutherford had supposedly published the results of the famous nitrogen-to-oxygen transmutation experiment. Campbell was unable to provide Krivit with a reference even though Campbell had been giving Rutherford credit for the discovery. Krivit followed the trail back to the original set of documents from the 1910s and 1920s. He found the published scientific paper. In doing so, he learned that Rutherford had conflated his discovery of the proton with Blackett's discovery of artificial transmutation and taken credit for both discoveries. Krivit reported his findings in his 2016 book Lost History.

The Conflation

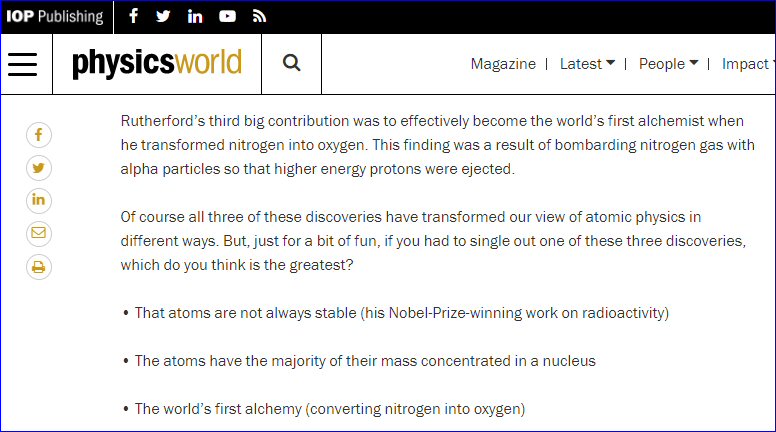

The physics community considers Rutherford one of the greatest scientists in the field's history. It had considered the first artificial transmutation discovery one of Rutherford's greatest discoveries, as a 2011 article in Physics World illustrates.

In Rutherford's 1917-1919 experiments, performed at the University of Manchester, he was looking for evidence of only what he would later call the proton. He used a scintillator to detect the proton, or, as he called it then, the "swift hydrogen atom." He reported his findings in a set of four papers published in 1919.

Rutherford's Assumption

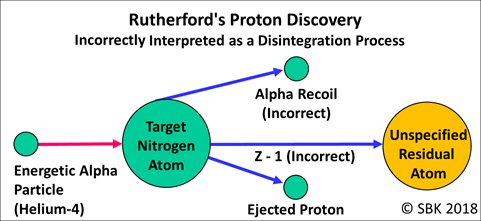

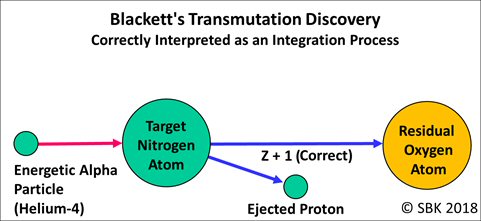

In the papers, Rutherford had hypothesized that the bombarding alpha particle knocked a proton off the target (a nitrogen atom), and the alpha bounced (more technically, recoiled) away from the target. This would have produced a three-forked set of particle tracks, as shown in the blue arrows in the diagram below. He did not, however, experimentally test this. He also made some wrong guesses about the residual atom.

Rutherford's incorrect assumption of the recoiling alpha is depicted with the upper blue line. Rutherford's incorrect assumption of an unspecified lower-charge residual atom is depicted with the middle blue line. Rutherford's correct observation of the ejected proton is depicted with the lower blue line. Rutherford knew that the scintillator he was using was not capable of qualitatively identifying the residual atom. His experiment therefore had no ability to determine the nature of the residual atom, or prove that a transmutation had taken place.

After Rutherford published his 1919 papers, he left Manchester to head up the Cavendish laboratory at the University of Cambridge. At Cambridge, Rutherford assigned the task of learning more about the fate of the residual atom to Takeo Shimizu. Rutherford instructed him to use another instrument, the Wilson cloud chamber, which was capable of recording particle tracks, thus providing the necessary experimental evidence to identify the transmutation process.

Wilson Cloud Chamber

Looking down into a modern Wilson-type cloud chamber with radioactive source in the center. Courtesy Ron Galli

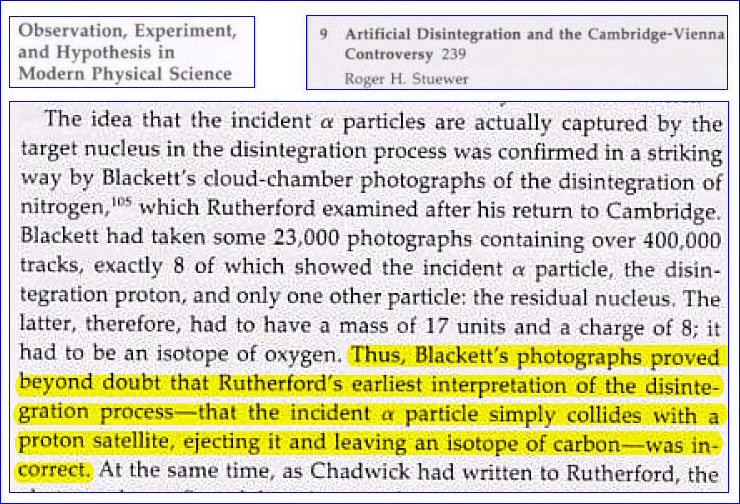

Shimizu had to return to Japan, and Rutherford reassigned the project to Blackett. After four years of work, and after photographing 400,000 particle tracks, Blackett had the answer. He observed and reported sets of not three, but two-forked tracks, confirming that the nitrogen atom captured the alpha particle, temporarily transmuting nitrogen into fluorine, then nearly instantly ejecting a proton and leaving a residual oxygen atom.

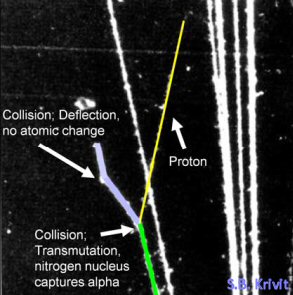

Photo by Blackett of an alpha-particle colliding with a nitrogen nucleus. The resulting oxygen nucleus goes left, and the proton goes right. (Color and annotations added by Krivit)

Rather than revealing a disintegration process as Rutherford had speculated, Blackett's experiments revealed that the impinging alpha particle resulted in an integration of the alpha particle into the nitrogen target.

Blackett correctly determined that the alpha entered the target nitrogen atom rather than striking and recoiling from it. Blackett observed and correctly determined that the reaction produced a higher-charge residual atom, and he published his conclusion that the nitrogen nucleus should have changed into an oxygen nucleus:

In ejecting a proton from a nitrogen nucleus, the alpha particle is therefore itself bound to the nitrogen nucleus. The resulting new nucleus must have then mass 17 and, provided no electrons are gained or lost in the process, an atomic number of eight. ... It ought, therefore, to be an isotope of oxygen.

The only reason he was tentative that it "ought" to be oxygen was that the oxygen-17 isotope had not been discovered yet! In any case, he reported the facts as he observed them.

This process is depicted in the diagram below with the middle blue line. Blackett had confirmed Rutherford's interpretation of the ejected proton, depicted with the lower blue line.

Roger Stuewer was one of the few historians who had correctly understood this and described it accurately in 1985. As Stuewer wrote, Blackett had, in fact, disproved Rutherford's interpretation of the process:

Rutherford's Report

In his 1919 papers, Rutherford had reported the results as best he could. He had no information about the identity of the residual atom and, being the meticulous scientist that he was at that time, made no assertions of transmuting one element to another.

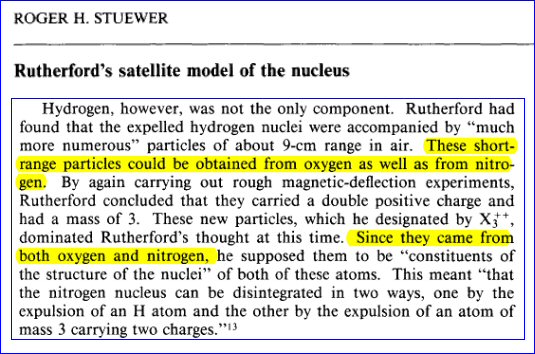

The following year, in his Bakerian lecture, delivered June 3, 1920, he speculated that a transmutation process was taking place and made some (wrong) guesses:

The expulsion of a mass 3 carrying two charges from nitrogen, probably quite independent of the release of the H atom, lowers the nuclear charge by 2 and the mass by 3. The residual atom should thus be an isotope of boron of nuclear charge 5 and mass 11. If an electron escapes as well, there remains an isotope of carbon of mass 11. The expulsion of a mass 3 from oxygen gives rise to a mass 13 of nuclear charge 6, which should be an isotope of carbon. In case of the loss of an electron as well, there remains an isotope of nitrogen of mass 13. The data at present available are quite insufficient to distinguish between these alternatives.

Discovery Credit

After Krivit began sharing his finding with scientific scholars, many of them concurred. Some responded quickly, others took many months to adjudicate the matter. Only a few scientific scholars argued with Krivit that Rutherford should retain credit for the transmutation discovery. This reasoning is not based on sound scientific ethics. These scholars defended their argument based on the fact that Rutherford's experiment would have caused such a transmutation, despite the fact that Rutherford didn't observe that result. He couldn't have. Rutherford didn't use an instrument capable of detecting the transmutation. He also didn't propose such a hypothesis or publish any such claim. Experimental discovery credit goes to the scientist who a) makes or measures the observation and b) reports or publishes it. That's what Blackett did.

Oxygen Confusion

Some science scholars also misunderstood the Rutherford 1919 papers. After Rutherford performed experiments in which he filled the test chamber with nitrogen, he filled it instead with oxygen and saw a similar type of particle emission. Historian Roger Stuewer described this correctly in 1986:

Mary Jo Nye, a Blackett historian, described the history correctly in greater detail in 2004. She did not, however, report the misattribution of the transmutation discovery credit.

Correcting the Myth

In January 2017, after the publication of Lost History, Krivit began an outreach program to inform the scientific and academic communities in an effort to correct the historical record. Krivit selected prominent organizations whose Web pages with the error ranked high in search results.

Sixteen months later, most of the organizations had made complete corrections. The group included scholars at the University of Manchester, Cambridge University, Imperial College, the American Institute of Physics, the Royal Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, Oxford University Press, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the Nobel Foundation. The table at the bottom of this page contains a full list of the original and corrected pages, as well as some of the acknowledgment letters Krivit received.

As the letters of acknowledgment show, Krivit found general concurrence. But there were a few disputes. The people who argued against Krivit's thesis helped to shed light on the confusion.

Carmen J. Giunta, Editor of the Bulletin for the History of Chemistry

Carmen J. Giunta disputed Krivit's conclusion that credit for the transmutation discovery belonged to Blackett. Giunta is the chairman of the Department of Chemistry and Physics at Le Moyne College. Giunta is also the editor of the Bulletin for the History of Chemistry and a member of the American Chemical Society’s Division of the History of Chemistry. Before knowing about Krivit's investigation into the transmutation discrepancy, Giunta had graciously agreed to review draft copies of chapters for Krivit's Lost History book.

But when he got to the chapter covering this transmutation history, Giunta disagreed with Krivit and believed that the credit should remain with Rutherford.

“After all,” Giunta wrote, “Rutherford did artificially transform nitrogen to oxygen, even though he didn’t know it at the time.”

Krivit argued with Giunta that credit for experimental discoveries should be assigned to the person who performs the experiment, obtains the evidence (the data), and publishes or reports that data to the scientific community. However, Giunta did not change his mind.

Karl Grandin, Historian for the Nobel Foundation

Karl Grandin, the historian for the Nobel Foundation, initially insisted to Krivit that "we think there can be no doubt that Rutherford first achieved nuclear transmutation in 1919, although he got the reaction somewhat wrong." Grandin told Krivit that, after Blackett completed his experiments, Rutherford "re-interpreted [his results] as oxygen-17 plus a proton."

Krivit was fascinated by Grandin's suggestion that Rutherford "re-interpreted" his results. Krivit provided citations for his sources to Grandin and asked Grandin to do likewise. Grandin didn’t respond. Instead, several days later, without any comment to Krivit, Grandin removed the transmutation discovery credit from the Nobel Prize biography Web page for Rutherford.

Grandin, however, was unwilling to credit Blackett on the Nobel Prize biography Web page for the discovery. Instead, he left the page giving credit to Blackett for making "the first photographs showing the transmutation of nitrogen into an oxygen isotope.” Grandin was unwilling to fully admit to Krivit that he had been mistaken so, on his direction, the Nobel Foundation diminished Blackett's role from "discoverer" to "photographer."

University of Manchester

In June 2018, Krivit contacted Sean Freeman, the head of nuclear physics, and Martin Schröder, the vice-president and dean of the University of Manchester. They soon corrected their Web page that contains this history, and Schröder sent Krivit a letter of appreciation. There was almost no argument, but this needs to be mentioned here as context for what will be described below.

The Institute of Physics, Education

In June 2018, Krivit also reached out to the office of Charles Tracy, the IOP head of education, to advise him of the incorrect version of this history on one of their Web pages. In later conversations, Krivit included Martin Andrew Whitaker, the chairman of the IOP History of Physics group. After a few e-mails, Krivit and Tracy arrived at a consensus, and Tracy changed the IOP's Web site to attribute the discovery to Blackett instead of Rutherford. Whitaker responded to one of Krivit's e-mails, and Krivit copied him on his final exchanges with Tracy. Whitaker had to have known the new information.

John Campbell, Rutherford Historian

In May 2019, five years after Krivit had his initial conversation with John Campbell, a Rutherford historian, Krivit reached out again to Campbell. Krivit provided his research to Campbell, and Campbell conceded that Rutherford should not have been credited with the transmutation of nitrogen to oxygen. Krivit and Campbell were able to come very close to consensus, although at this point, Campbell was still implying that Rutherford observed an elemental transmutation; not to oxygen, but to hydrogen.

“In the future, I will be more careful and not summarize it as that he turned nitrogen into oxygen but use what was known in 1919, that he turned nitrogen into hydrogen,” Campbell wrote.

The Institute of Physics History of Physics Group and Robin Marshall

Around that time, in May 2019, when Krivit had reconnected with Campbell, Krivit learned that a group of retired scientists was planning the "Centenary of Transmutation" at Manchester, to take place in early June. The group included members of the U.K. Institute of Physics History of Physics group (HOP) and Robin Marshall, a Manchester professor emeritus.

The two organizers, Neil Todd and Peter Rowlands, had arranged the meeting to celebrate what was going to be, they believed, the 100th anniversary of Rutherford's 1919 artificial transmutation discovery at Manchester. They didn't realize that the artificial transmutation discovery actually took place in 1925, was performed and reported by Blackett, and that he had done so at the University of Cambridge. Thus, they were planning to hold a grand celebration for the wrong scientist, in the wrong year, at the wrong university. Krivit's new information was horribly inconvenient.

If Whitaker did tell his peers in the HOP group about the exchange between Krivit and Tracy, then the members decided as a group to ignore the new development. Krivit reached out to the organizers to alert them of the impending mistake. Unsurprisingly, they and, more specifically, Marshall were unreceptive to Krivit's new information. More precisely, they were outraged at what they perceived as Krivit's malicious intent to interfere with their event. But the event took place — almost as planned.

Freeman Speaks

On June 8, 2019, Professor Sean Freeman opened the session. (Krivit had already briefed him a year earlier, and they had come to near consensus.) Five minutes after he began speaking, Freeman informed members of the audience that the historic transmutation discovery took place 94 years earlier, by Patrick Blackett, at the University of Cambridge. Freeman knew the truth and he was not going to play games with it. The audience learned that Rutherford’s 1919 accomplishment was limited to the discovery of the proton.

Campbell Speaks

After Campbell spoke, members of the audience were perplexed about what seemed to be an incongruity between the advertised purpose of the meeting and what they were now hearing. That's because none of the organizers had informed the audience that the entire premise for the celebration was a mistake. (Krivit hired a videographer to record some of the talks and the recordings preserve these awkward moments .) Campbell repeatedly and accurately responded to the confused audience that Rutherford never claimed that he had transmuted nitrogen to oxygen.

Campbell ended his talk with a mea culpa and explained that he had misunderstood the history. The audience's questions reveal the obvious: The audience had come to hear about transmutation. Freeman, as Campbell had, unambiguously explained that no such event took place at Manchester. Campbell admitted that he never carefully read Rutherford’s original scientific papers. Instead, Campbell admitted that he relied on secondary sources:

I found out much more about that since I wrote my book. I just assumed that the people writing about Rutherford who knew him were right, but then I’ve found out they never looked at the article — I assumed — records of the day, and just formed their own guesswork.

Marshall Tweets

Robin Marshall did not take the news as willingly as Campbell. Three days before the “Centenary of Transmutation” meeting, Marshall wrote on his Twitter account that he had submitted a review of Krivit's analysis to an unnamed journal in an attempt to show that Krivit was wrong and that the discovery credit should remain with Rutherford — and Manchester. Marshall complained on Twitter that the editor had rejected his review. Marshall resorted to posting his entire review, as screenshots, to his Twitter feed. Undaunted, Marshall took his rejected paper and expanded it into a small book, in which he did his best to defend Rutherford's and Manchester's title to the transmutation discovery.

They Did It Their Way

Two years later, in October 2021, the IOP-HOP group published a special issue of its newsletter. It is 102 pages and called "The Centenary of Transmutation." It contains the historical record that the event's participants have chosen to leave behind.

It includes Freeman's statement during his opening remarks that "Blackett thus became the first person to reveal the details of the process – i.e., of alpha particle capture with the ejection of a proton to leave a residual nucleus of oxygen."

It includes the opening statement from Neil Todd who, contradicting Freeman, said "It is fitting that a meeting in June 2019 … celebrate the centenary of Rutherford’s 1919 discovery of a new physical process, that of artificial transmutation ..."

In his statement, Todd had unknowingly revealed his fundamental misunderstanding, saying that Rutherford "had also determined in the part III paper that the heavy recoil atom following the induced disintegration of nitrogen had a range of that of oxygen." [Emphasis added]

Campbell Gets It

But Campbell understood this better by then. He said Rutherford had said that "the range of the recoiling nitrogen atoms is about the same as the oxygen atoms." It wasn't exactly what Rutherford had written, but Campbell expressed the main point correctly. The difference from what Todd said is subtle but critical, as will be explained in a moment.

Campbell concluded his discussion of the history: "Patrick Blackett ... in 1925, showed that the disintegration of nitrogen by alpha particles occurred by alpha capture and proposed that what was left behind after the ejection of a proton was a rare isotope of oxygen-17."

Marshall Misses

Marshall explained his understanding of the history: "The initial state consisted of the elements helium and nitrogen, and the final state consisted of the element hydrogen and something which careful reading of the two papers shows, behaved more like oxygen than nitrogen." He had not read the papers carefully.

Here is the entire concluding paragraph written by the "Centenary" organizers Neil Todd and Peter Rowlands:

Given the amount of time that has passed since Rutherford’s discovery of artificial transmutation and the ever-increasing volume of material that the science generates, it is understandable, if lamentable, that the history of it has become confused. We, as co-organizers of the 2019 meeting and co-editors of this volume, are very pleased that the articles presented here within collectively enshrine Rutherford’s 1919 discovery of artificial disintegration / transmutation in its rightful place in the history of physics.

When Marshall had written his critique of Krivit's thesis and submitted it to a journal, he included this statement:

Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with helium nuclei and observed the production of hydrogen nuclei and noting with surprise that the main recoil nucleus behaved more like oxygen than nitrogen, thereby irrefutably demonstrating nuclear transmutation, changing one element into another and becoming the world’s first successful alchemist. [Emphasis added]

Todd, Rolands, and Marshall didn't understand the experiment. Here's what Rutherford wrote:

We have drawn attention in Paper III to the rather surprising observation that the range of the nitrogen atoms in air is about the same as the oxygen atoms. (Rutherford, Collisions IV, p. 586, ¶ 1) [Emphasis added]

Campbell Nails It

By then, Campbell knew that there was nothing in Rutherford's four 1919 papers about a residual nucleus that he chemically identified as oxygen. Nor could there have been: Rutherford used a scintillator, not a cloud chamber.

Campbell understood that Rutherford had filled the chamber with different gases during different experiments, sometimes filling it nitrogen and sometimes with oxygen. Rutherford was comparing the range of the expelled particles when using nitrogen targets versus the range when using oxygen targets.

Erasing History: U.S. Department of Energy

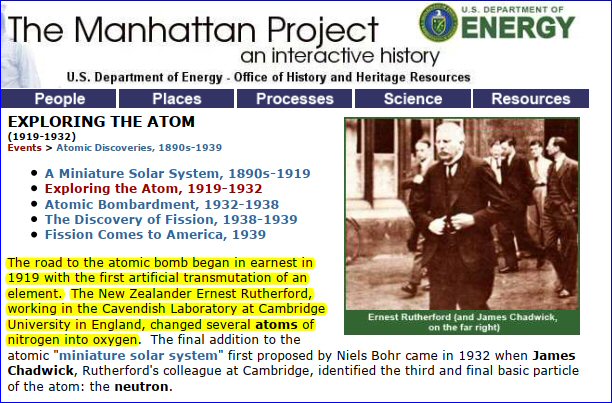

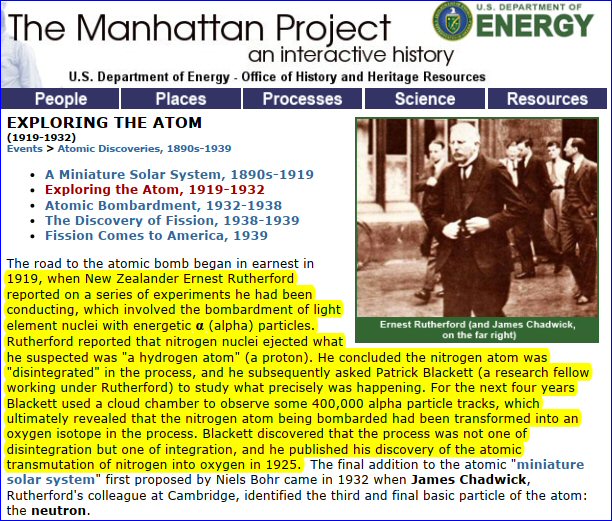

One of the first people Krivit had contacted in his outreach in 2017 was Dr. Eric W. Boyle, Chief Historian for the Department of Energy, who now works in the DOE's Office of Legacy Management. This is what the relevant section of the DOE's Web page looked like:

On March 14, 2017, Boyle wrote back to Krivit:

Thank you for this thorough and conscientious reply and for all of the information and citations related to this history. I will analyze the matter with my colleagues, and if our conclusion is similar to your conclusion, we will make the corrections. As this is a website hosted by another unit within DOE, and in partnership with our Office of Classification, this process will have to go through a couple of reviews before the changes are made. We will also be evaluating this page with a number of other pages so the review won't proceed until everything is ready for one bulk submission.

Seven months later, on Oct. 11, 2017, Boyle presented Krivit with a draft of his proposed revision. They had arrived at a consensus. DOE had accurately corrected the page:

On Oct. 11, 2017, the sources for the DOE page looked like this:

The reference from the AIP went to this page, which says:

So where did the myth of Rutherford’s 1919 transmutation originate? Steven Krivit tells this story in his Lost History: Explorations in Nuclear Research, vol. 3, chapter 23. He traces the beginning of the myth to newspaper articles in that year and then to Rutherford’s reaction in 1925 to results by his younger colleague, Patrick Blackett. Krivit correctly credits Blackett with observations that showed the process of transmutation in action. For more detail on this fascinating story, see Krivit’s book.

Three and a half years later, on March 12, 2020, Boyle contacted Krivit again:

Unfortunately, I have some not great news. I’m writing to give you some advanced warning that I’ve decided I’m going to have to retract the revisions made to the website regarding Blackett and Rutherford.

Several months ago, I was contacted by an award-winning physicist who is familiar with Rutherford’s work. He told me the language in the revision was inaccurate, historically and scientifically. He provided extensive primary source evidence to corroborate his interpretation of the events.

As a result, I starting doing some more research. After reading a lot about this episode, and consulting with another physicist who is familiar with Rutherford, as well as two highly respected historians of science who have written about Rutherford’s work at the time in question, I’ve determined that the text for the "Exploring the Atoms" page needs to be revised once again. There is consensus that the current language is problematic, including the suggestion that a "Rutherford myth" persists.

Krivit discouraged Boyle from making the retraction. After some discussion with Krivit, Boyle, and Kristen Holmes, Boyle's supervisor, Holmes personally took charge of the matter. Holmes and Boyle decided against reverting the discovery back to Rutherford. Instead, they completely removed all mentions of the transmutation discovery from the DOE "Exploring the Atoms" Web page. No credit to Rutherford, no credit to Blackett, just an erasure of one of the most significant discoveries in the history of physics.

On one side, Krivit had pressured the DOE to make its depiction of science history accurate. On the other side, an anonymous "award-winning physicist who is familiar with Rutherford’s work" and two anonymous "highly respected historians of science who have written about Rutherford’s work" had pressured DOE to remove the discovery credit that DOE, in response to Krivit's assistance, had rightfully attributed to Blackett. Instead, the DOE had colluded with the Rutherford historians: If Rutherford was no longer the rightful claimant of this discovery, then DOE was not going to give the credit to Blackett, which he rightfully deserved.

The top of the page then reverted to this:

At that time, the sources for the DOE page then reverted to this:

The DOE had removed three sources: The AIP Web page, the Galison reference and the Krivit reference. The first remaining reference was F. G. Gosling, The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb (DOE/MA-0001; Washington: History Division, Department of Energy, January 1999. On page 1, that document begins with the incorrect version of this science history:

The anonymous Rutherford experts had managed to manipulate the DOE to revert to the false version of this history and to misattribute the credit for this discovery. Perhaps someday the DOE may choose to communicate this history more accurately.

A summary page for the Manhattan Project history also lists Rutherford, in 1919, for being the first to transmute one atom into another. As of Krivit's letter to DOE on Oct. 19, 2022, DOE had not made any changes to this page:

The Birth of High-Energy Physics

Blackett's discovery of the first confirmed artificial nuclear transmutation led directly to the next logical step, the particle accelerator. In 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, at the Cavendish laboratory, built the first apparatus for accelerating atomic particles to high energies. They reported the first man-made transmutation by artificially accelerated particles: the disintegration of lithium by fast hydrogen protons. This breakthrough established the new field of high-energy physics.

References

1. Nye, Mary Jo, Blackett: Physics, War, and Politics in the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press (October 30, 2004)

|