| George Miley, a pioneer in the low-energy nuclear reactions field and an emeritus professor at the University of Illinois, made an extraordinary claim of excess heat on Oct. 20, 2011, at the World Green Energy Symposium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A person who attended the symposium filmed Miley's presentation and uploaded it to YouTube. At 17:57 in this video, Miley states, "At the moment, we can run continuously at levels of a few hundred watts."

New Energy Times spoke with Miley in December and learned that his data showed a peak of eight Watts of excess heat over a period of 100 seconds. Apparently Miley misspoke.

The Potential of LENR

Miley's claim of running continuously at levels of a few hundred watts of excess heat would be a commercially viable level of energy production. In 23 years of LENR research, only a handful of scientists have made such a claim. Unfortunately, nothing practical came of those claims, including the work Miley did with James Patterson of Clean Energy Technologies Inc..

The good news is that everything known about LENR indicates that it has practical potential. The big question is, When will it be realized in LENR-powered devices and machines? Is the latest Miley claim an early indicator? Is it based on well-documented science? This New Energy Times investigation and analysis, and exclusive interview with Miley, provides insight.

Miley's Distinguished History

Few people have such a distinguished history with low-energy nuclear reaction research as Miley. From the beginning of the cold fusion controversy in 1989, he courageously testified before Congress and encouraged exploration of LENR.

For 15 years, Miley was the editor of the American Nuclear Society's Fusion Technology journal. He modeled integrity in science journalism and stuck his neck out where few others would dare. He agreed to publish valid LENR research that other editors summarily rejected. He was also keenly sensitive to how some of science media treated cold fusion researchers unfairly.

For many years in the 1990s, Miley was one of the very few American LENR researchers who worked with nickel and hydrogen rather than palladium and deuterium. Most people in the field believed that Ni-H LENR could not be caused by nuclear fusion. Peter Hagelstein, for example, who has worked on LENR theories for 23 years, clearly understood this when he discussed the weak-interaction-based models which " more closely match[ed] the experimental observations."

But when the popularity of weak-interaction-based models passed in the mid-1990s and the cold fusion models dominated the field again in 2000, Miley held his ground. He was not limited to the constraints of the belief that deuterons were overcoming the Coulomb barrier at room temperature - that is, cold fusion. Miley was one of the first people who also began using the term "low-energy nuclear reactions," as he wrote to me.

"To my knowledge," Miley wrote, "I am the first to use the term LENR when I first reported my transmutation experiments."

In the early 1990s, this wasn't much of a conflict in the field with competing ideologies because even American "cold fusion" believers Hagelstein and SRI International electrochemist Michael McKubre realized that LENR likely was not caused by fusion. For reasons that are still unclear, McKubre and Hagelstein switched their focus back to the cold fusion hypothesis by 2000.

And when they did, clearly knowing that light-hydrogen LENR disproved their hypothesis of cold fusion, they revealed their skepticism toward Miley's Ni-H work. Their attitude toward light-hydrogen LENR is perhaps best exemplified by Hagelstein's statement on Aug. 14, 2008, spoken in front of most of the members of the field at an international conference in Washington, D.C.

"Light-water excess heat. Is it real? Randall Mills claims observation of it," Hagelstein said. "Mitchell [Swartz] has seen light-water excess heat. [Francesco] Celani's report is on light-water excess heat. But if it’s real, what's the reaction scheme look like? My current understanding of the reaction scheme is that I'm not sure what comes in. I'm not sure what comes out. I don't know how much energy is made, and I don't know how it works. Other than that — "

The rest of Hagelstein's comment was drowned out by the audience's laughter.

A month earlier, in July 2008, I published my in-depth investigation of biophysicist Francesco Piantelli's groundbreaking light-hydrogen LENR research. I wrote that " deuterium and palladium were not required." I wrote that Piantelli had achieved levels of excess heat and energy from light-hydrogen LENR that the rest of the field had never seen with deuterium. Seven months earlier, in January 2008, I had introduced the Widom-Larsen not-fusion theory.

Miley's expertise is in nuclear measurements. He has not been well-recognized in the field for calorimetry. His current calorimetry work may be poorly documented, but much of his earlier LENR transmutation work provided seminal contributions to the field, as I explained in my interview for IARPA. On request from New Energy Times, Lewis Larsen, one of the developers of the Widom-Larsen ultra-low-momentum neutron theory of LENRs, provided a comment about this work.

"Miley's transmutation work in the mid-1990s was brilliant and was responsible for my entering the field," Larsen said. "In my early due diligence before I formed Lattice Energy LLC, I showed Miley's five-peak spectrum to two senior scientists with a major Department of Energy laboratory. I had asked them to assist me with my due diligence of the field. They concurred with my assessment that Miley's five-peak transmutation spectrum was real.

"In 2002, my company sponsored research by Miley and his group at the University of Illinois and by Andrei Lipson and Alexei Roussetski at the Institute of Physical Chemistry with the Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Lebedev Physics Institute. They performed crucial calibrations and measurements of high-energy charged particles in light-water electrolytic cells that formed a benchmark for solid-state nuclear track detector (CR-39) measurements performed by numerous LENR researchers in the last decade.

"Miley's unique light-water five-peak transmutation spectrum was mirrored by Tadahiko Mizuno's heavy-water data. The set of data allowed Allan Widom and I to develop our theoretical model, which shows that the five-peak mass spectra was a unique signature of ultra-low-momentum neutron absorption."

Miley's 2011 Work

At the time when Miley gave his presentation in the World Green Energy Symposium, interest in Rossi's claims had peaked. Miley, too, seemed interested in associating his own work with Rossi and his Ni-H claims, as seen by similar slides he presented at a NASA Workshop on Sept. 22, 2011. For nearly the entire year, Rossi dominated the LENR news headlines and caused many people to believe that LENR research was further along than it is. Some bloggers got the impression that Miley was eager to follow the Internet media blitz created by Rossi.

But on Nov. 15, Miley's postdoctoral researcher, Xiaoling Yang, spoke on the phone with several business associates, according to a person who was on the call. According to Yang, Miley's group had performed only one experiment that demonstrated a significant excess-heat effect, and in that one experiment, the effect lasted for only a few minutes.

Two days later, I sent an e-mail to Miley and asked for his comment on the apparent discrepancy. I asked him whether he could provide any scientific information or data for his claim of being able to "run continuously at levels of a few hundred watts." I also asked him for details about how his group performed its calorimetry.

Miley did not answer any of my questions. Instead, he gave me a response that was vague and unrelated to my questions. I replied to him and questioned why he appeared to be reporting a claim without supporting scientific data.

"You are jumping to conclusions," Miley wrote. “All [my] statements [are] based on experiments shown.”

I asked him where he had shown the data.

"All is on the slides that I showed," he wrote. “As I said earlier, we now are developing data for a publication.”

I had found copies of his slides on the Internet. On Nov. 28, I asked him for a phone interview so he could help me avoid any incorrect assumptions and help me to learn clearly about his experiments and data. I clarified to him that my focus was on the work he reported on Oct. 20, not any new data that he was developing. Miley agreed to a phone interview, but he declined my invitation to schedule a specific day and time for it.

On Dec. 3, in the absence of a chance to learn from Miley directly in a phone call, I began looking at his slides. I saw some things that seemed to explain the discrepancy. I sent Miley another inquiry.

I asked him, "When you said, 'At the moment, we can run continuously at levels of a few hundred watts,' did you omit to state at the end of that sentence 'per kilogram of material'? In other words, would it have been more correct to say, 'At the moment, we can run continuously at levels of a few hundred watts per kilogram of material'"?

I also asked him three other questions:

- Do the data in your slides show a measured power rate of about 2 watts average?

- Do these slides show calorimetry data from more than one recent experiment that produced excess heat?

- In the experiment referenced on slides 19 and 20, does the calorimetry data from this experiment show an experimental duration of 400 seconds?

By Dec. 6, I had received no response from Miley. I sent the questions to him a second time. I also copied the message to Robin Kaler, associate chancellor for public affairs for the University of Illinois. The next day, Miley agreed to schedule a phone interview with me. We spoke on Dec. 8.

I present my notes from our dialogue below. I will intersperse some relevant commentary with the dialogue.

Krivit: Let's start with the question I asked you in the e-mail. When you stated "At the moment, we can run continuously at levels of a few hundred watts," did you omit to state at the end of that sentence "per kilogram of material"?

Miley: That was with 20 grams of nanoparticles.

Krivit: So my question was, Were you actually running at several hundred watts output or several hundred watts per kilogram of material? Are you talking about a direct-power measurement or a power-density measurement?

Miley: That's watts per gram.

[I wanted to check with Miley to see whether other data in his slides might have shown any experiment that produced levels of a few hundred watts of excess heat.]

Miley: We don't have that in there. We’re still working on that. I don't want to discuss that yet.

[I asked the question to him a second time to make sure we were not misunderstanding each other. I got the same answer. I told Miley that it seemed inconsistent. In his e-mail, he said he had shown the data in his slides; now I learned that the data was not in the slides.]

Miley: All we want to disclose at this time is what is in the slides.

Krivit: But during your video presentation, you said you could run continuously at several hundred watts.

Miley: That is correct, but I didn't show the data for it.

Krivit: And you have the data for that which you can show?

Miley: I don't want to show it, but let me explain this experiment.

Krivit: Well, you have a major inconsistency here.

Miley: Fine, but let me explain this experiment. There are some important features that might not be obvious to someone.

Miley explained the experiment to me. Essentially, it is a replication of the Arata-style gas-loading experiment that has been replicated by a number of LENR researchers, particularly at Kobe University, Japan. New Energy Times reported on this in 2008. The Kobe researchers also published their results in Physics Letters A in August 2009.

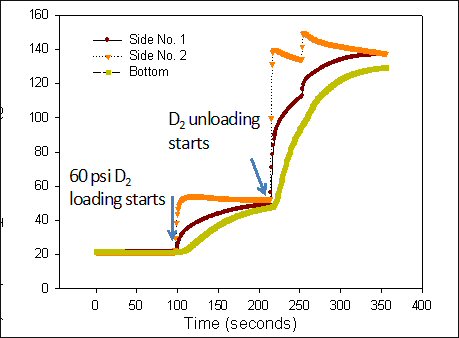

On Miley's slide #19, he shows one experimental run. He shows temperature data from three thermocouples within the cell. At 100 seconds, deuterium gas begins to flow into a chamber containing palladium nanopowders. The temperature rises from 20 degrees C, steeply at first and then flattening out at about 50 degrees. This is the expected behavior from a chemical, exothermic reaction. The temperature holds steady at that level for 100 seconds.

Miley June 2011 Gas-Loading Pd-Nanopowder Experiment

At 200 seconds, they switch the gas valve. This relieves the pressure, and the deuterium deloads from the palladium. At this point, based on ordinary chemistry, the expected result would be an endothermic reaction; the experiment should cool. Instead, the temperature jumps rapidly to about 130 and flattens out there. Miley does not show data past 350 seconds, so what happened next in that experiment is unknowable. Miley calculates the chemical capacity of the first phase (100-200 seconds) as 690 Joules. He calculates the energy of the second phase (200-300 seconds), based on the time and temperature, as 1,479 Joules. The net gives the excess energy, 789 Joules.

This is one of many excellent demonstrations of an anomalous source of energy in LENR research. Examples like this may not provide enough energy to boil a cup of tea, but many world-changing technologies have evolved from similar early research.

But as one editor to another editor, I had difficulty with Miley's refusal to show his data.

Krivit: George, let me ask you a question. You've been a science editor for many years. If someone came to you and submitted a paper to a journal and said, "We're getting a certain level of performance, but we're not going to show our data," what would you tell them?

Miley: This is different. I'm not submitting a paper to you.

Krivit: You made a presentation at a science conference.

Miley: I made this presentation at several different meetings.

Krivit: So is there a difference in the protocol if you make a presentation at a science conference versus submitting a journal paper?

Miley: Yes. A paper is going to go out to peer reviewers, and they would ask, "Where's the evidence?" That's why I don't want to talk about it until I submit a paper to journal.

Krivit: But it's OK to make these claims at a science conference?

Miley: What you do in a meeting is different from what you do in a peer-reviewed journal publication.

Krivit: Have you already submitted this work to a journal?

Miley: No, I have to get more data.

Krivit: If this whole thing is premature, and if you have to get more data, was it premature for you to say that you could run continuously at levels of several hundred watts?

Miley: No. We've done that, but I didn't say for how long. I don't want to get caught in the big mistake like Pons and Fleischmann did. History says, if you disclose things prematurely, you can really get in trouble. All we wanted people to know was that we always get significant excess energy like you see in the slide and that we run continuously over a limited time.

Krivit: By my calculations, you get a net of 789 Joules, right?

Miley: Yes, over a period of 100 seconds.

[When I looked at Miley's data before our phone call, I had assumed that the full period for the data was 400 seconds. The difference, in this case, is irrelevant.]

Krivit: So what power does that come to?

Miley: That's 8 Watts. But this was not our run that demonstrates the energy. That's why this slide is labeled "triggering an excess-heat measurement."

[Slide 19 is actually labeled "Preliminary Excess-Heat Measurement Using Our Gas-Loading Calorimetry System"]

Krivit: People have asked me about your claims of several hundred watts of excess heat. What am I supposed to tell them?

Miley: Tell them that I haven't disclosed the data and I won't until I publish it in a reviewed journal and I've finished all the experiments. If I disclose it now, I'm doing it prematurely because we haven't finished all the experiments.

Krivit: But it sounds like a take-back because you got people all excited with these news stories about you getting hundreds of Watts of excess heat and now you're saying this. It doesn't sound like you're being fair to people.

Miley: I think I'm being fair to people because I don't want to disclose things until I have completed the refereed paper. We're looking at hydrogen as well as deuterium, and all these things require finding the sweet spot to control long continuous runs, and we’re working at it. It takes time, especially when you have no funding.

[According to Miley's slides, his work is funded by the New York Community Trust and NPL Associate Inc.]

Krivit: When was this recent gas-loading experiment performed?

Miley: That slide that shows the data was done about three months ago.

[Miley's NASA slides says that the experiment was performed in June.]

Krivit: Was that before the NASA Glenn meeting?

Miley: We had done one experiment before that meeting, but I don't know if it's the same one. They have very similar data; they were repeatable.

Krivit: You mean every time you tried you were able to get a result?

Miley: Yes, within 10 percent or so. The nanoparticles take a long time to make. We make our own.

Krivit: And these experiments are being performed at the University of Illinois?

Miley: Yes. You can see the picture of the students. We have three undergraduates and one graduate student working, but they only work a few hours a day. But we don't have funding, so it’s not a high-priority activity. We're trying to raise money.

Krivit: When might be the earliest you'd submit this to a journal?

Miley: We are waiting on more material to make new nanoparticles. We have run four different compositions through. We want to try one more set. That may take a few months to get ready.

Miley: If you're going to criticize me in your story, Please make sure to state that our plan is not to disclose the data until we have a peer-reviewed journal publication. Our field has suffered greatly from people who have prematurely done things, and I don't want to get in that trap.

After my interview with Miley, I quickly checked on the Internet to see whether he had made any other claims about his recent experiment. I found something from LENR researcher Dennis Cravens. I remembered that Cravens had initially heard the Miley excess-heat rumor from Hagelstein as well as from McKubre. Cravens had told me that he had contacted Miley to find out whether the rumors were true and that Miley had confirmed them.

On Dec. 13, I sent Cravens an e-mail and asked him what Miley had told him. He sent me a copy of an Oct. 24, 2011 e-mail that Miley had sent him.

"Yes, we are getting some good gas-loading results at the 100s of watt level!!" Miley wrote.

On Dec. 29, 2011, Cravens sent me another e-mail.

"I think that George has found a mistake in his grad student's work," Cravens wrote. "She was rushing due to the baby delivery."

|